The internet is drowning in dashcam footage. Zero percent of it can train Physical AI.

The reason: none of it knows where it is. A world model doesn't just need to see a crosswalk — it needs to know it's at 37.4281°N, 122.1777°W, at 28 mph, at 4:31 PM on a Wednesday. Without that, video is just pixels. You can't build a map from it. You can't train a planner on it.

This is the core problem the Bee solves: positioning. Get it wrong and everything breaks — a pothole tagged to the wrong lane is worse than no data, a speed limit on the wrong segment corrupts every downstream decision. No amount of scale fixes inherited error.

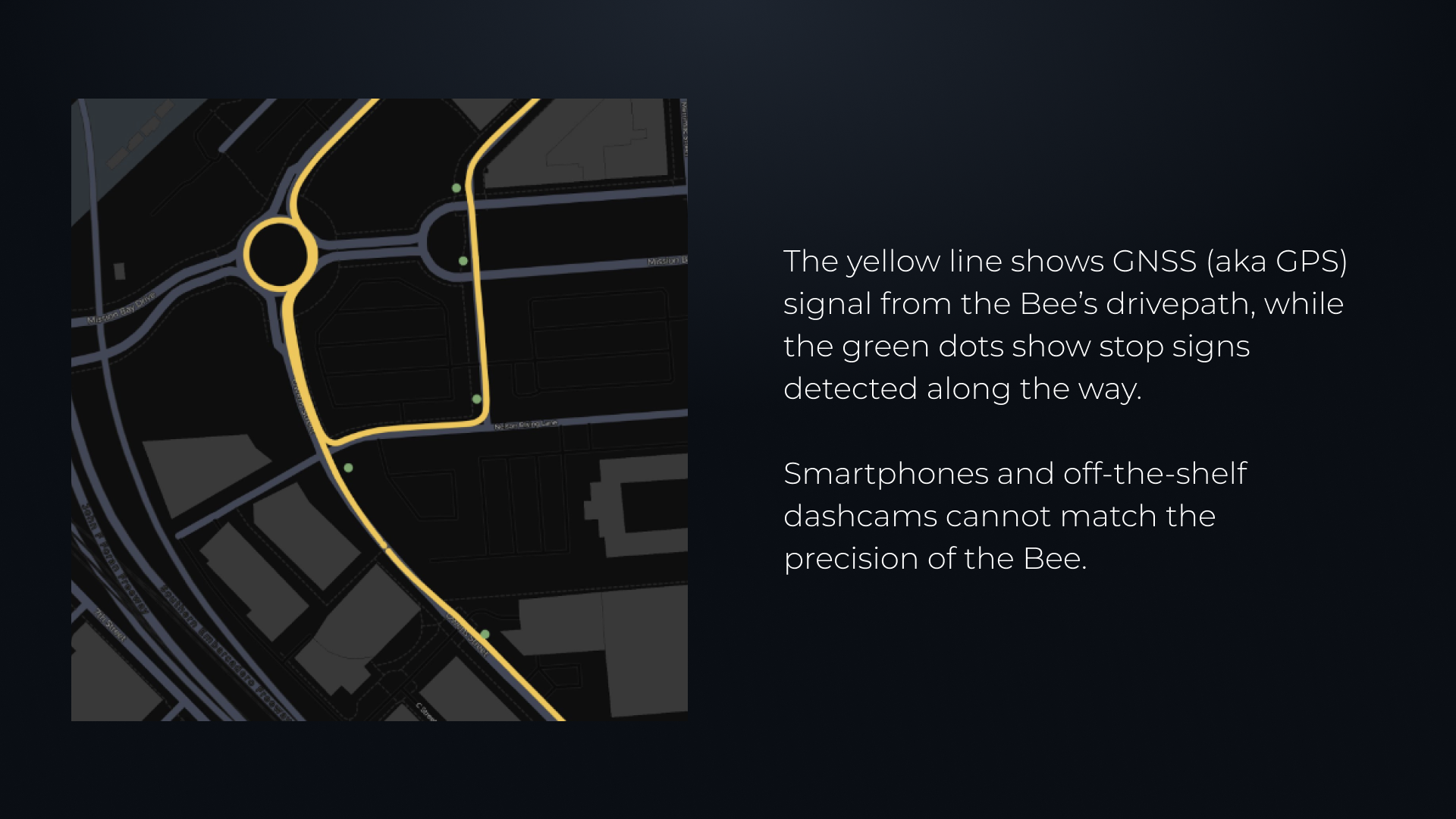

The video below was captured by a Bee on the I-210. Click "Show Map" to see the GNSS trace — every frame tagged with coordinates, speed, and acceleration. This is what spatially grounded video looks like.

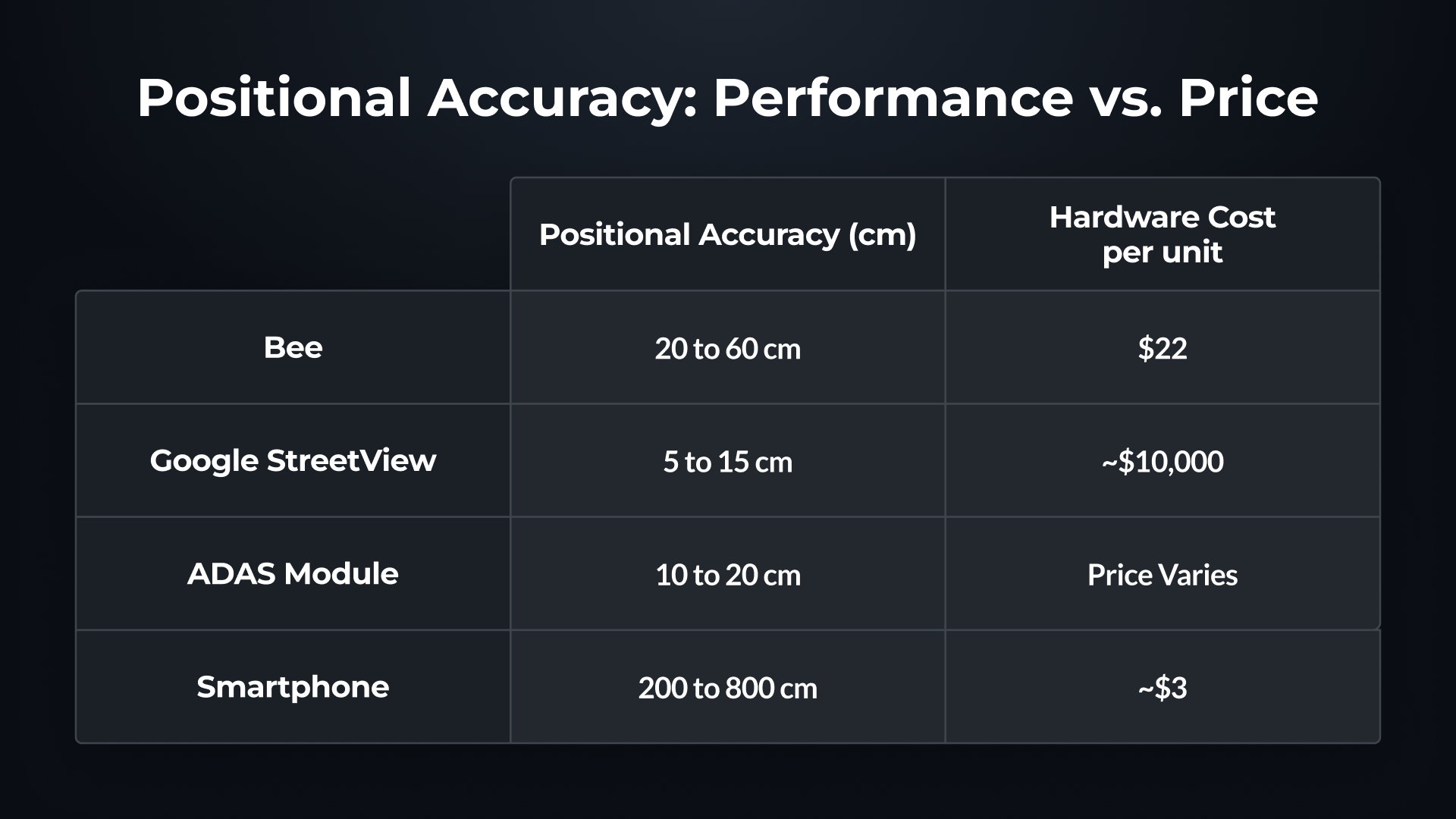

The gap between "good enough" and "actually useful"

GPS is good enough to get you to a restaurant. It is not good enough for machines to reason about the physical world. Most crowdsourced mapping efforts have quietly failed in that gap.

Think about what actually happens: you detect a stop sign but place it 15 meters from where it actually is. The detection was right. The classification was right. The coordinates were wrong — and that made the whole observation useless. For an autonomous vehicle, this isn't a rounding error. It's a fundamental breakdown.

The reason is surprisingly simple: hardware. In cities — where mapping matters most — buildings bounce satellite signals off glass and steel, shifting position by 10 to 30 meters. Smartphones try to solve this with a 5mm antenna. Consumer dashcams aren't much better. You can't fix a 5mm antenna with better software. You need better hardware.

We wrote about this more broadly in There is nothing like a Bee. When we designed the Bee, we made positioning the central design constraint — not a peripheral feature. Everything else was organized around one question: how do we make this device know exactly where it is?

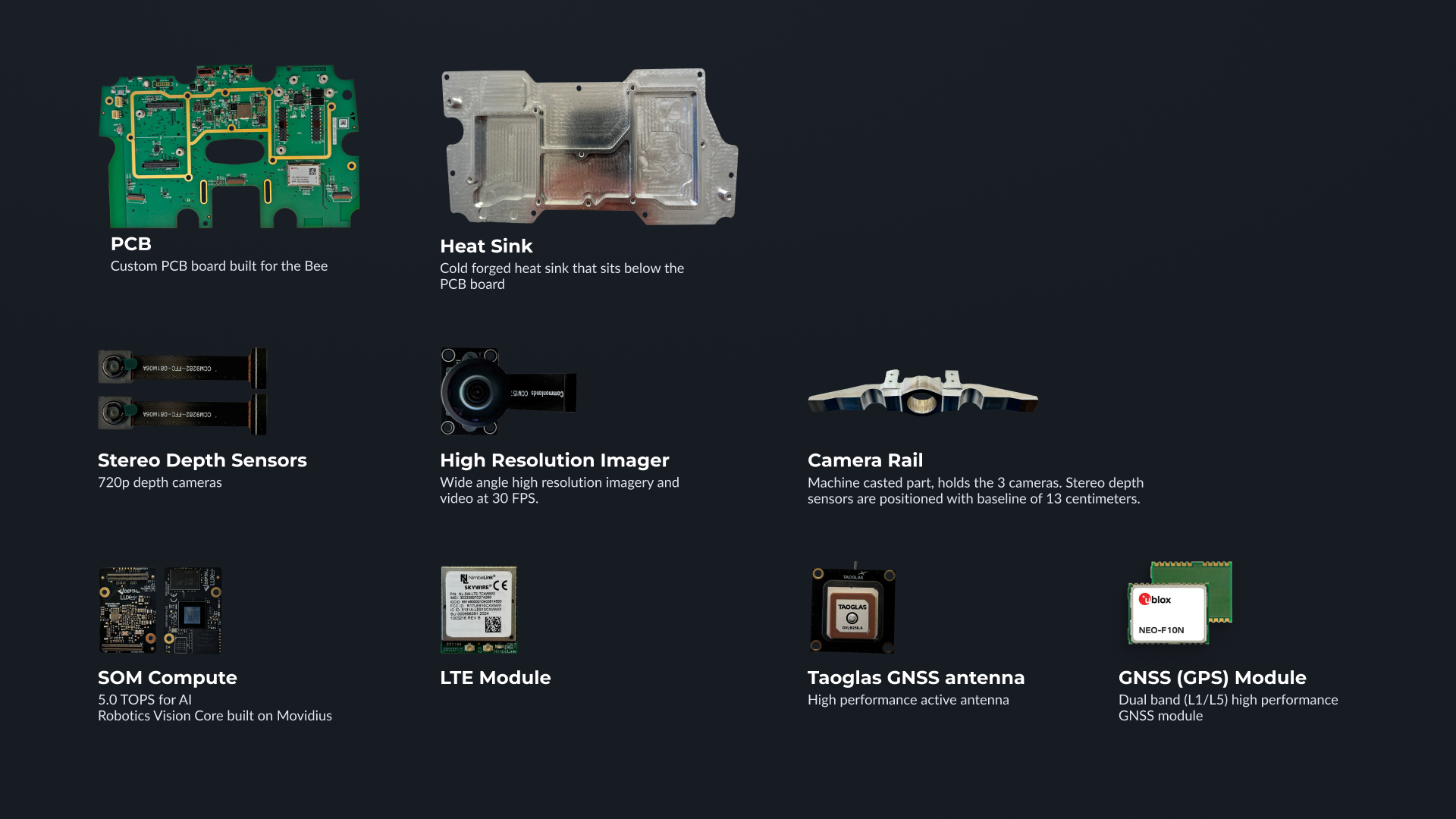

Five sensors, one position

The approach we settled on involves five independent sensor systems that cross-reference each other. I want to walk through each of them, because I think the details matter and because the interaction between them is where the real accuracy comes from.

1. The GNSS receiver

The Bee uses a u-blox NEO-F10N, which is a dual-band module receiving signals on both the L1 and L5 frequencies from GPS, Galileo, and BeiDou constellations simultaneously. The L5 band is the important part here — it was designed specifically with improved resistance to multipath interference, meaning the receiver can better distinguish a direct satellite signal from one that bounced off a building. This is a meaningful upgrade over the single-band receivers in phones and consumer dashcams, and also over the NEO-M9N we used in earlier hardware.

2. The antenna

This is the component I think is most underappreciated. The Bee uses a Taoglas dual-band active antenna mounted on a 70x70mm ground plane — roughly the size of a credit card. That's an order of magnitude larger than what fits in a smartphone (~5x5mm) and substantially larger than a typical dashcam antenna (~10x10mm).

A bigger ground plane means better signal reception, less multipath contamination, and more reliable satellite lock in marginal conditions. It's the kind of boring, physical-world tradeoff that doesn't show up in a spec sheet comparison but makes a real difference in practice. The Bee can afford to devote this much space to the antenna because it was designed for one job; a smartphone, which needs to fit a screen, battery, cellular radio, and camera array into a thin slab, cannot.

3. The inertial measurement unit

A six-axis IMU — an accelerometer and gyroscope — continuously measures the device's orientation and motion in three dimensions. When satellite signals degrade (in a tunnel, under a bridge, in a narrow street between tall buildings), the IMU enables dead reckoning: estimating how far the device has moved and in what direction based on inertial data alone.

This fills what would otherwise be gaps in the position trace — the jumps and discontinuities you see in smartphone GPS tracks when you drive through a parking structure or under an overpass. The IMU also tells the system exactly how the camera is oriented relative to the road surface, which turns out to be essential for the next piece.

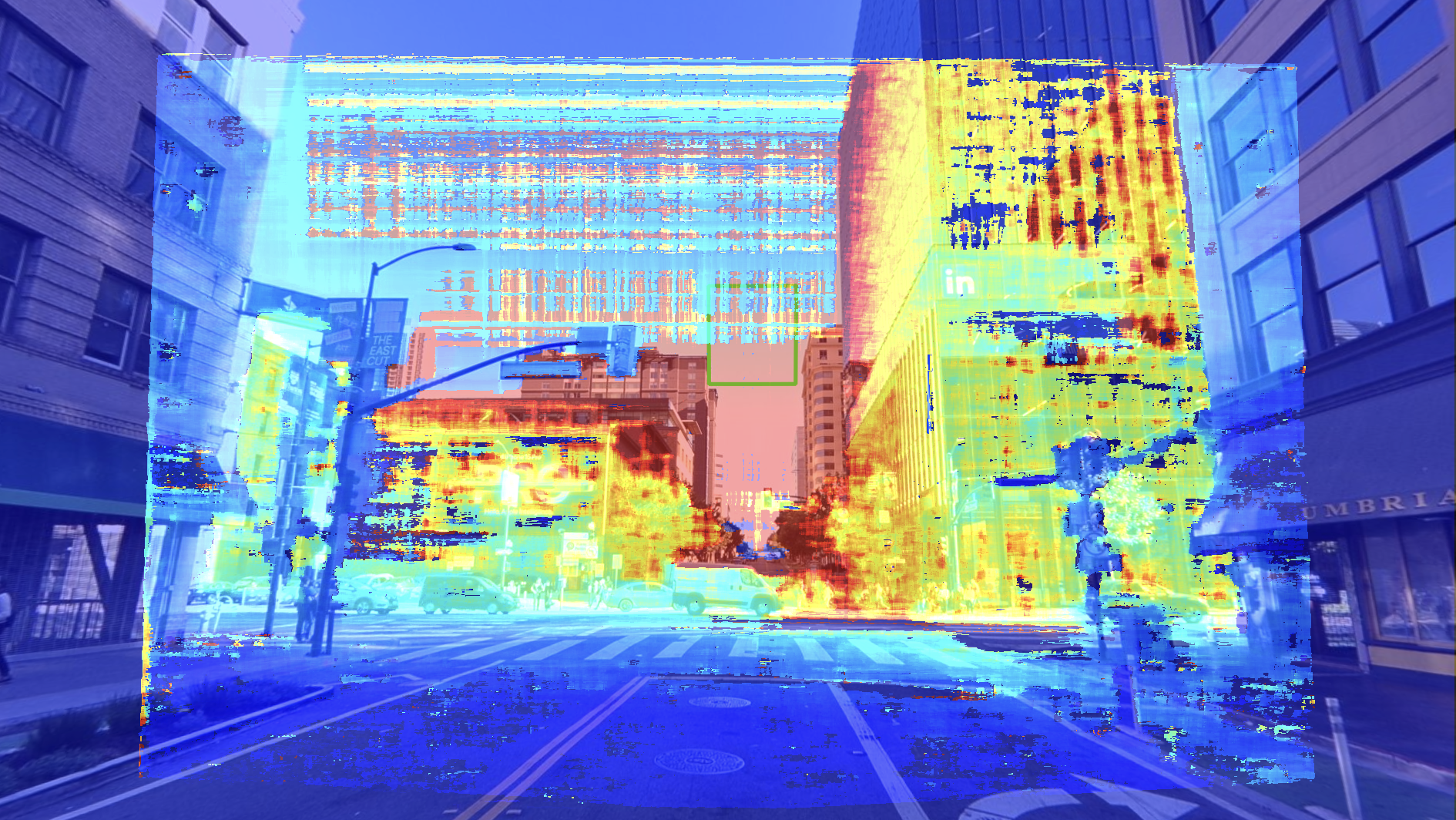

4. Stereo depth cameras

This is where things get interesting. The Bee has two 720p cameras separated by 13 centimeters — roughly the distance between human eyes — that generate depth maps through stereo disparity. This gives the device something that no single-camera system has: an independent measurement of how far away things are.

When the system detects an object — a stop sign, a lane marking, a traffic light — the stereo cameras can estimate that it's, say, 12.3 meters ahead and 2.1 meters to the right. This is a spatial reference that's completely independent of satellite positioning. Even if the GPS is temporarily degraded, the stereo system maintains a sense of where things are in three-dimensional space relative to the device.

Combined with the GPS and IMU data, it creates a kind of redundancy that I think is qualitatively different from just having a better GPS chip.

5. Visual odometry and ML mounting detection

ML algorithms determine the Bee's exact mounting position and angle on the vehicle (which varies from car to car and installation to installation), and optical flow — tracking how pixels move between consecutive frames — provides a frame-to-frame motion estimate that supplements both GPS and IMU. This is a third independent source of movement information, which means that no single sensor failure can silently corrupt the final position.

What sensor fusion actually means

I should be clear that none of these sensors are independently sufficient. A GPS receiver, even a good one, will still drift in urban canyons. An IMU accumulates error over time. Stereo depth is precise at short range but degrades with distance. Visual odometry can be confused by repetitive textures or sudden lighting changes.

The key insight — and I think this is the part that makes the Bee's positioning genuinely different from what came before — is that these failure modes are largely uncorrelated. GPS degrades when buildings block satellites; the IMU doesn't care about buildings. The IMU drifts over time; the GPS corrects it every time it gets a clean satellite fix. The stereo cameras lose accuracy at range; but they're most useful precisely in the near field, where they can catch lateral drift that the other sensors might miss. And the ML mounting model ensures that every projection from camera coordinates to world coordinates is geometrically correct, even if the device is mounted at an unusual angle.

The positioning pipeline fuses all of these data streams continuously, weighting each sensor according to its current confidence. The result — and I want to be careful not to overstate this, but I also think the evidence supports it — is lane-level positioning as a practical reality on real roads, not just as a theoretical spec.

We tested this directly in downtown San Francisco, which is about as challenging an urban canyon environment as you'll find in North America. We ran an interior-mounted Bee alongside an exterior-mounted device using RTK corrections — the industry gold standard, which typically requires roof-mounted hardware and a monthly service subscription. The Bee, sitting behind the windshield with no external corrections, tracked closely with the RTK-corrected device.

I don't want to claim it was identical, and there's ongoing work to push accuracy further, but the gap was small enough to validate the approach: you can get remarkably close to professional-grade positioning using onboard sensor fusion alone, without requiring any external correction service.

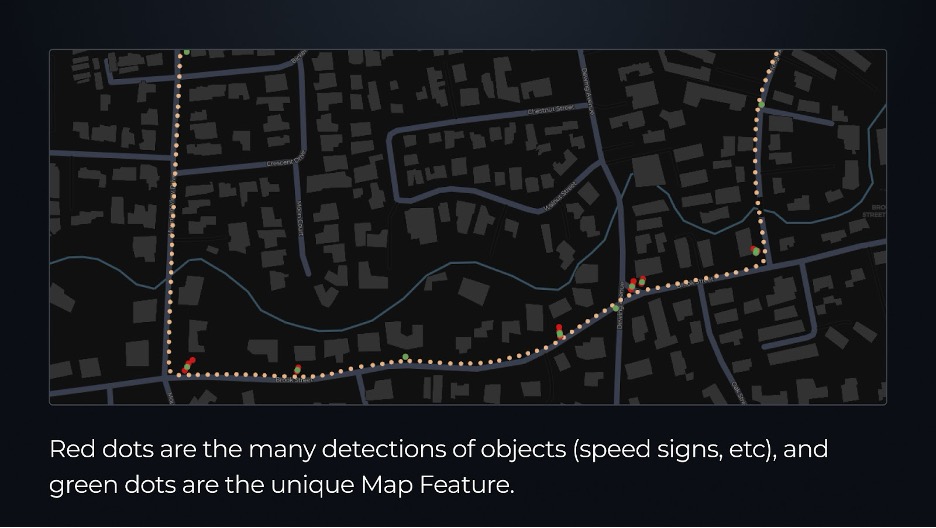

The drive path above is a real example

The imagery playing above this post was captured by a Bee on a summer afternoon near Stanford, California — driving through the tree-lined residential streets adjacent to campus. The 124 frames span about two and a half minutes of driving, including a turn and a stretch heading back in the opposite direction.

If you click "Show Map," you can see the drive path overlaid on the actual street. What I'd draw your attention to is the smoothness of the trace — the coordinates progress steadily along the road with no lateral jumps, no sudden shifts, no implausible position changes. The path follows the road geometry precisely, frame after frame, even through the turn.

The regularity of that path is, I think, the most intuitive demonstration of what good positioning looks like in practice. It's not interpolated or post-processed; it's what the sensor fusion pipeline produced in real time.

Every frame includes its exact coordinates and timestamp, and you can query this imagery programmatically through the Bee Maps Road Intelligence API.

Why this matters beyond mapping

I want to close with a few thoughts on what I think accurate positioning actually enables, because I believe the implications extend well beyond making better maps — though that alone would be worthwhile.

Autonomous vehicles. Volkswagen's ADMT division chose Bee Maps data for its ID.Buzz robotaxi program in Hamburg, and the specific use case is telling: they needed precise curbside positioning for pick-ups and drop-offs. A few meters of error in a map means the autonomous vehicle pulls over in the wrong lane, or stops where there's no curb cut, or blocks a bus lane. Lyft made a similar assessment when they licensed Bee Maps data for routing and AV strategy.

Change detection. I think this is one of the more subtle and important capabilities. If your positioning is accurate to the lane level, you can detect not just that a sign exists at a location, but that it has moved two meters from where it was last week. The real world is defined by small, incremental infrastructure changes, and you need very good positioning to distinguish a genuine change from sensor noise.

Fleet safety. For Beekeeper customers, precise positioning means knowing exactly where an AI-detected event happened — not "somewhere on this block," but "in this lane, at this point in the road." That level of specificity transforms a data point about harsh braking from an abstract statistic into a concrete observation about a specific road condition.

Without lane-level positioning, a system might attribute the vehicle to the wrong road entirely — or flag a false positive against a lower surface-street speed limit.

3D reconstruction. The stereo depth data combined with accurate GPS opens the door to building spatial models of the real world detailed enough for robotics, simulation, and augmented reality. I think this is still early, but the foundational capability is there.

A quick comparison

For readers who want the summary:

| Bee | Smartphone | Consumer Dashcam | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GNSS | Dual-band L1/L5 | Single-band | Single-band |

| Antenna | 70x70mm ground plane | ~5x5mm | ~10x10mm |

| Depth Sensing | Stereo (13cm baseline) | None | None |

| IMU Fusion | 6-axis, fused for mapping | Available, not used for mapping | Typically absent |

| Positioning Class | Lane-level | Multi-lane drift | Multi-lane drift |

| Edge AI | 5.1 TOPS NPU | Limited | None |

I think the central point here is architectural, not just a matter of better components. The Bee wasn't designed as a dashcam with GPS added on; it was designed as a positioning system that also captures imagery. That inversion of priorities is what makes the difference, and it's what I think ultimately determines whether crowdsourced maps can be trusted by the systems — autonomous vehicles, fleet management platforms, navigation services — that increasingly depend on them.