The Network is Buzzing

The inversion: maps come from AI world models, not the other way around

There is a deeply ingrained assumption in the mapping industry that the output of a mapping system is a map: a static artifact composed of geometries, labels, and attributes—lanes, signs, speed limits, turn restrictions—that downstream software can query and render. This assumption is breaking.

The frontier of spatial AI is not better static maps. It is AI world models grounded in real world coordinates: systems that do not merely represent what exists at a location, but learn to predict what happens there. The key input to those systems is not surveyed geometry or manually labeled point clouds. It is sensor-grounded video.

What maps can't capture

Traditional HD maps encode lane topology, signal phases, right-of-way rules, and regulatory context with impressive precision. Navigation systems, ADAS stacks, and autonomous vehicle planners all depend on this data.

What they do not encode is behavior that enable us to make predictions about a given location.

At a given intersection, drivers typically wait for two or three oncoming cars before taking the unprotected left. Pedestrians routinely cross against the signal on one corner during the evening commute. Right-turn-on-red may be legal, but almost no one takes it because sight lines are blocked by a delivery truck that appears most weekday mornings.

This is the knowledge human drivers acquire through experience. It is temporal, probabilistic, and contextual. It cannot be captured by static geometry alone. You learn it by observing the world unfold.

Video as the highest-bandwidth sensor

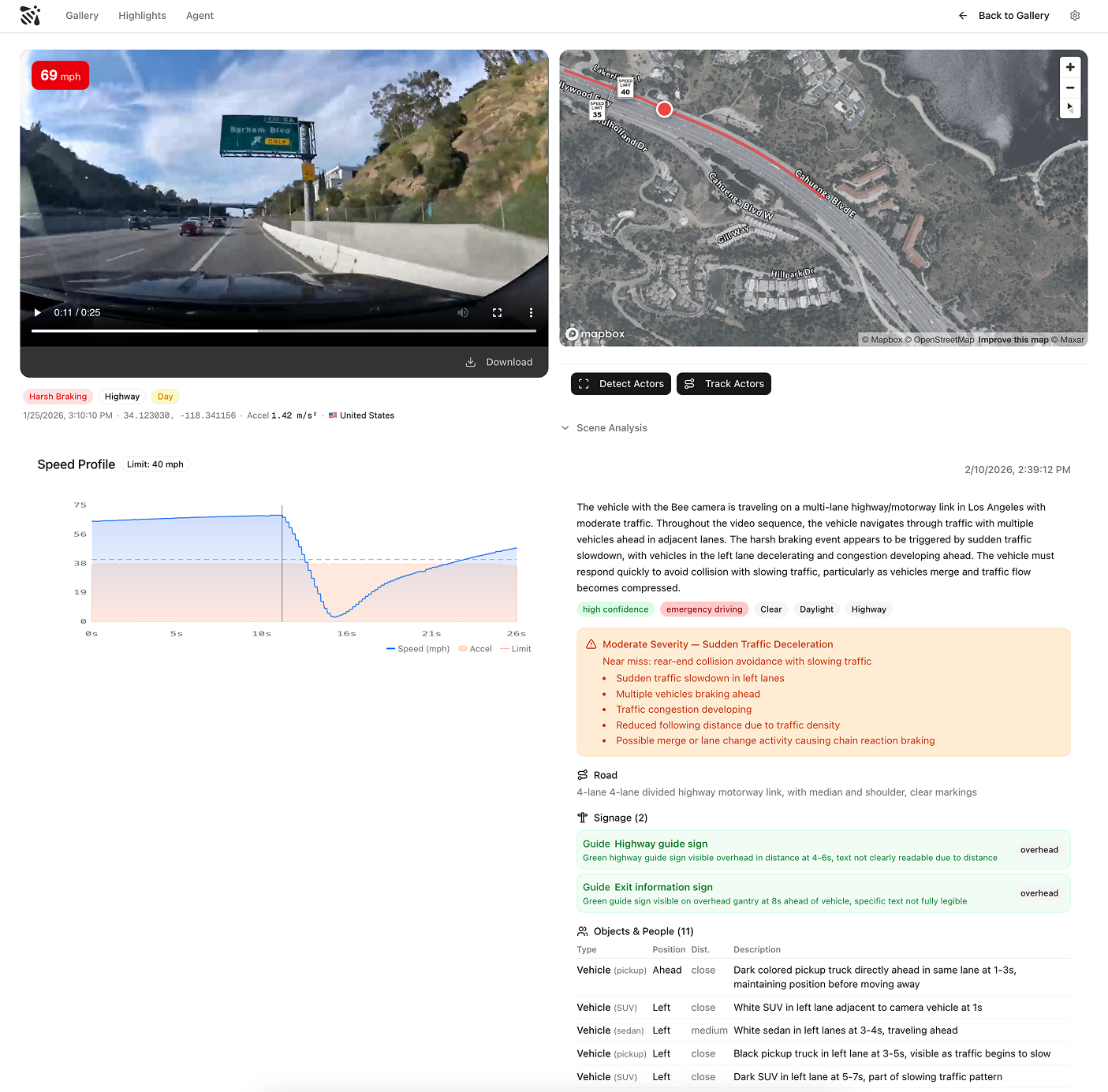

A video clip captured by the Bee at a high-information moment - hard braking, evasive steering, complex intersections, dense highway merges, and more - is an unusually rich data artifact, but only when paired with precise vehicle sensor data.

A single 30-second AI event video, synchronized with GNSS positioning, IMU measurements, vehicle speed, and calibrated camera intrinsics, captures:

- Physical structurelane layout, signage, signal state, surface conditions

- Scene dynamicspositions, velocities, and trajectories of all visible actors

- Behavioral causalitywho yielded, what triggered the maneuver, whether the response was typical

- Environmental contextlighting, glare, weather, visibility

- Precise location and timingexactly where and when the event occurred in the physical world

This is not an abstracted description of reality. It is a sensorimotor record of a real moment. Without accurate positioning, inertial data, and timing, video is ambiguous. With them, it becomes a grounded sample of how the world actually behaves.

From perception to prediction

Modern vision models already extract structured perception from this data. Given synchronized video frames and telemetry, they can reconstruct what happened: objects, motions, interactions, and triggers.

That is useful, but it is not a world model.

A world model answers a different question: what happens next?

If the approach speed is higher, what is the probability of a full stop? If it is raining at dusk, how does pedestrian behavior change? How does local driving culture alter merging behavior on this curve?

Training systems to answer these questions requires large volumes of real, diverse, sensor-grounded driving data. Short, information-dense clips are especially valuable because they concentrate the moments where prediction is hardest and consequences are highest.

The inversion: maps come from world models, not the other way around

If you train a world model on enough sensor-grounded video—clips tightly synchronized with GNSS positioning, IMU, vehicle speed, and calibrated camera intrinsics—the model necessarily learns physical structure as part of learning dynamics. You cannot predict merging behavior without encoding curvature and lane topology. You cannot model pedestrian crossings without internalizing crosswalk geometry, signal timing, and sight-line constraints.

The result is not a hand-authored map. It is a learned spatial representation that can be queried, rendered, and projected into traditional map views when needed. Explicit maps stop being the primary source of truth. They become derived products—views extracted from a behavior-first world model, grounded in real sensor data rather than static annotation.

This reverses the traditional pipeline. Historically, we built maps first and then used them to inform intelligent systems. A model trained on enough real driving video will learn road structure on its own — because it can't make good predictions without it.

Scale is the moat

Building a world model that generalizes across the planet requires video from across the planet.

Highways in Phoenix and San Francisco are not enough. Real generalization requires residential streets in Wrocław, roundabouts in Bangalore, unmarked intersections in Lagos, school zones in Tokyo. Each geography encodes different norms, heuristics, and failure modes.

A large, distributed camera network becomes AI infrastructure. Each camera samples the behavioral distribution of the physical world. Each AI event video captures a moment where prediction is difficult and therefore valuable.

The advantage compounds with scale, diversity, and sensor quality.

Traditional Maps | AI Event Videos | |

Captures behavior | Geometry only | Full scene dynamics and geometry |

Sensor depth | Surveyed structure | Video + IMU + GNSS + speed |

Cost curve | Manual, expensive | Automated, declining |

What the map becomes

The map of the future still tells you the speed limit is 35, that the next exit is 24B, and that the light ahead has a protected left-turn phase. You still need the basics.

But it also answers a question that no static map can: what usually happens here?

What is likely to happen at this intersection at 5:30 PM on a rainy Friday in January? Eighty percent of vehicles approaching this merge from the right lane at 45+ mph brake within 200 meters. In rain, that rises to ninety-five percent. On weekday mornings, a delivery truck blocks the sight line at this corner and drivers skip the right-on-red entirely.

The structural layer — geometry, signage, regulation — remains essential. What changes is that it's no longer sufficient on its own. The next layer is behavioral, learned from millions of sensor-grounded observations, and it's the layer that makes prediction possible.

Video is the training data. Sensors provide the grounding. The map is what the model learns — structure and behavior together.

AI Event Videos are available via REST API and MCP server for AI agent integration.

See the Technical Reference for data schemas, sensor specs, and integration guides.

Also, check out some sample videos here.